Prostate cancer can be a scary diagnosis for any dog owner, and rightly so. While less common than some other cancers in dogs, it’s often an aggressive disease. In this blog we will help you understand what prostate cancer is, how it’s diagnosed, and the treatment options available for your furry companion.

What is Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer is essentially an uncontrolled growth of cells in a dog’s prostate gland. While some growths can be benign (non-cancerous), most prostate tumors in dogs are malignant (cancerous, or neoplastic). These malignant tumors are typically very aggressive and have a high chance of spreading away from the prostate to other parts of the body.

Why Does it Happen?

The exact causes of prostate cancer in dogs aren’t fully understood. While in men, hormones play a big role, in dogs, prostate cancer can develop in both neutered and unneutered males. Ironically, studies suggest it might even be more common in neutered dogs. This is a bit of a mystery, but one idea is that neutered dogs tend to live longer, giving cancer more time to develop. Genetics may also play a part in the development of prostate cancer.

As is in men, age is the most important risk factor with older men (greater than 50 years old) being at higher risk, and older dogs (older than 8 years old) having a greater chance of developing cancer.

Certain breeds appear to have a higher probability of developing prostate cancer, including Doberman Pinschers, Shetland Sheepdogs, Scottish Terriers, Beagles, Miniature Poodles, Airedale Terriers, German Shorthaired Pointers, and Norwegian Elkhounds.

Recognizing the Signs:

What to Look For

Prostate cancer can cause a variety of symptoms, and they might not always seem directly related to the prostate. Keep an eye out for:

- Urinary problems: Difficulty urinating (straining, pain), frequent urination, blood in the urine, or leaking urine (incontinence).

- Digestive issues: Straining to poop, constipation due to the prostate compressing the colon.

- Lameness or weakness: This can happen if the cancer has spread to the bones, particularly in the hind limbs or spine. You might notice your dog seems stiff, painful, or has trouble walking.

- Generally feeling poorly: Lethargy, loss of appetite, or weight loss can be signs of advanced disease.

- Discharge: Bloody discharge from the penis or prepuce.

How is Prostate Cancer Diagnosed?

If your vet suspects prostate cancer, they’ll likely recommend a series of tests:

- Physical Exam: A rectal exam (feel prostate with finger) is part of your vet’s thorough physical, allowing them to feel the prostate. An enlarged prostate, particularly with urinary symptoms, warrants investigation. It’s important to distinguish between neutered and unneutered dogs: unneutered dogs commonly develop benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH)—an age-related benign enlargement o the prostate. Therefore, an enlarged prostate in an unneutered dog may be BPH. However, if your dog was neutered (especially at a young age), an enlarged prostate is a significant concern for cancer.

- Blood and Urine Tests: Basic blood work is often normal, but sometimes a high white blood cell count can be present. Urine tests might show blood or infection, and sometimes even cancer cells.

- Imaging:

- X-rays: Can show an enlarged prostate, and are crucial for checking if the cancer has spread to the lungs or bones. Mineralization in the prostate is a strong red flag.

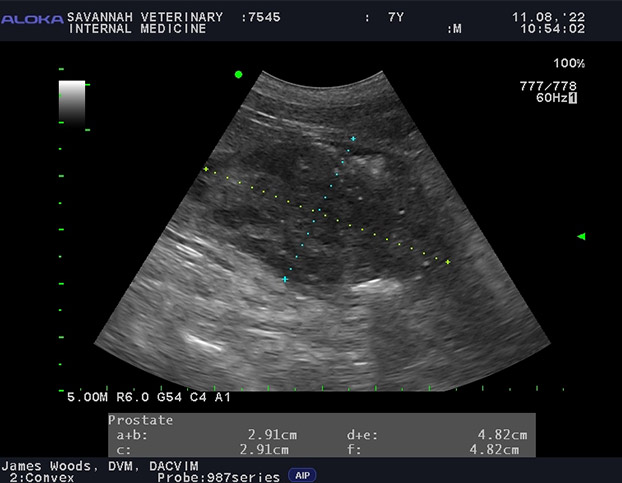

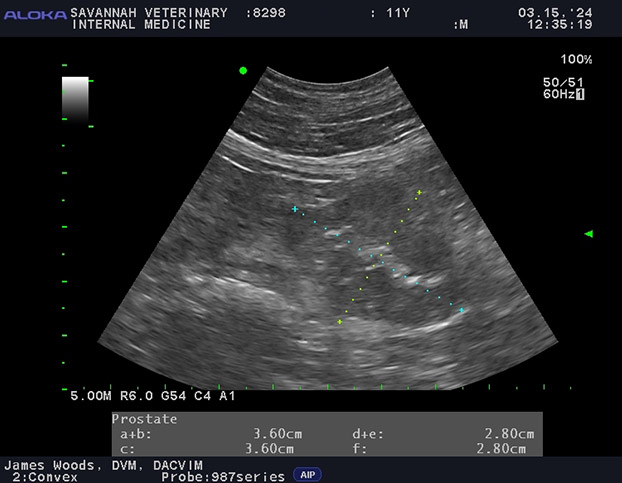

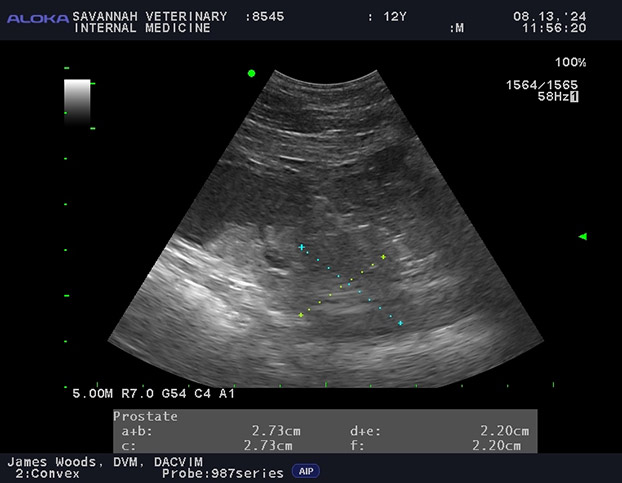

- Ultrasound: This is a great tool for getting a detailed look at the prostate, surrounding organs, and lymph nodes.

- Imaging Continued:

- Advanced Imaging (CT scan/MRI): These provide even more detailed images and are often used to plan treatment.

Treatment Options: What Can Be Done?

Treating prostate cancer in dogs can be challenging because it’s often diagnosed at an advanced stage. The goal of treatment is usually to improve your dog’s quality of life and extend their life.

- Surgery (Prostatectomy): While surgery to remove the prostate might seem like a good idea, it’s often not recommended due to the high rate of metastasis (spread) at diagnosis and potential complications like urinary incontinence.

- Radiation Therapy (RT): Radiation designed to target the tumor precisely while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues are available.

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy drugs can be used alone or in combination with other treatments. While not always a cure, chemotherapy can help manage the disease and improve quality of life.

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Certain NSAIDs, like piroxicam, can have anti-cancer effects and may help improve survival times in some dogs with prostate cancer, especially when combined with other therapies.

- Supportive Care:

- Pain Management: Pain relievers are important, especially if the cancer has spread to the bones.

- Antibiotics: To treat any secondary urinary tract infections.

- Urethral Stents: If the tumor is blocking the urethra and making it difficult for your dog to urinate, a stent can be placed to keep the urethra open.

- Cystostomy Tube: In severe cases of obstruction, a tube can be surgically placed to allow urine to drain from the bladder.

Monitoring: Treatment Response, Quality of Life

Regardless of the treatment chosen, regular monitoring is essential. This typically involves:

- Routine Vet Visits: To assess your dog’s overall health and clinical signs. Notify your vet if your dog is having difficulty urinating, having bloody urine or seemingly painful when urinating.

- Ultrasounds: Every few months to check the prostate and look for spread to lymph nodes and other abdominal organs.

- Chest X-rays: To screen for lung metastasis. Be mindful of new coughing symptoms, X-rays are important in this situation.

- Blood tests: Especially if your dog is receiving chemotherapy.

- Urine tests: To be sure that your dog has not developed a secondary urinary tract infection.

Contact Us

A cancer diagnosis for your beloved dog is incredibly difficult and stressful. However, with early detection and a comprehensive treatment plan tailored to their needs, you can help ensure they have the best possible quality of life for as long as possible. If your dog is showing symptoms of prostate disease, don’t hesitate to contact us. We’re here to help guide you toward an accurate diagnosis and support you every step of the way.

Author:

James Woods DVM, MS, DACVIM (SAIM)

Ph: (912) 721-6410

Contact Us